In 2016, Carla Harward’s daughter, Sophie, came home from her middle school in Chattooga County and told her mother about two students who hadn’t eaten over the weekend.

“I was stunned,” says Harward. “Sophie said the little boys were crying because their bellies hurt. We just had no idea there were kids in our community that were hungry.” Harward and some families gathered food for the family, but she knew more had to be done.

It was her daughter who mentioned all the food going to waste at her school and asked her mom a simple question: Why couldn’t they give families the food from her school instead of throwing it away?

Sophie’s idea became the spark that launched the Georgia nonprofit Helping Hands Ending Hunger, which now works with 150 schools throughout the state to divert food waste.

And there’s a lot of food going to waste. A 2019 USDA School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study found that 31 percent of vegetables and 41 percent of milk were tossed.

But those figures are changing. Schools in Atlanta are working to feed hungry families and rethink how they approach school food. Here are three making huge environmental impacts.

Helping Hands Ending Hunger

Harward thought her daughter’s idea to repurpose the food kids didn’t eat sounded simple, but the USDA has strict rules on preventing cold cafeteria food from being saved.

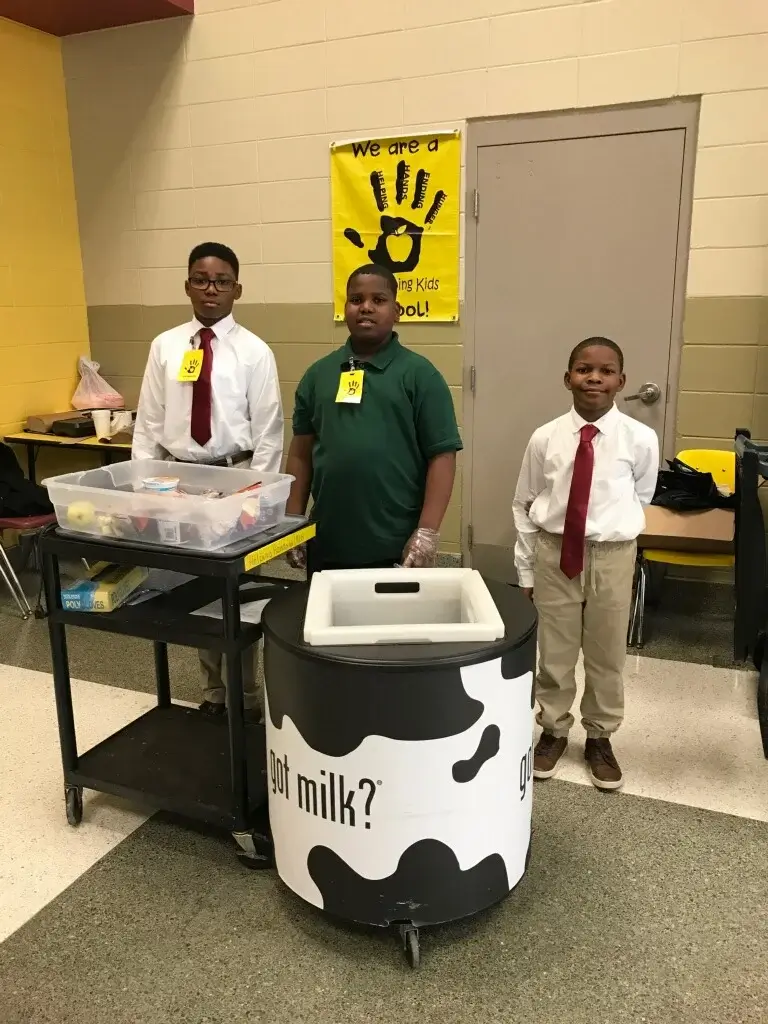

But Harward wasn’t deterred. In 2016, she formed a 501(c)(3) and tested the pilot in her daughter’s school. After lunches, students collected uneaten prepackaged food or dry goods, such as apple sauce, packaged carrots, and unopened milk cartons. The students learned how to safely collect and store the unused food, and then handed it out weekly to families in need.

In Georgia, that included more than 13 percent of children who lacked access to healthy food in 2022 (the latest numbers available), according to the nonprofit Feeding America.

Today, the Helping Hands program is in 150 Georgia schools and is run by students. “We now train volunteers and school staff at every school chapter to teach kids that food is not trash,” says Harward.

Students at Atlanta Public School’s Springdale Park Elementary School (SPARK) STEAM program rescued about 700 pounds of food between February and May 2024 alone, according to Harward. It was repurposed into 566 meals and another 486 pounds of food for the community.

“Food that can’t be saved is collected in compost buckets in the cafeteria and used in our [rooftop] garden; nothing goes to waste,” says Kristin Siembieda, STEAM program specialist and Helping Hands coordinator at SPARK.

Harward says the program works incredibly well. “These kids are taking charge and are going to be amazing future leaders.”

Food Waste Warriors

The students at Gwinnett County School’s Lovin Elementary have a warrior mentality when it comes to food waste.

In 2018, Gwinnett Clean & Beautiful’s Green and Healthy Schools had a rare opportunity to participate in a new initiative of the World Wildlife Fund, the Food Waste Warriors program.

“The World Wildlife Fund was looking for systems to collect data for its first food waste report, and to help write curriculum around how to do food waste audits,” says Gwinnett Clean & Beautiful board member Jay Bassett, who also works for the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “The Green and Healthy Schools program was already established [at Gwinnett County Schools], so we did it.”

In 2019, Gwinnett County Schools enlisted Lovin Elementary in Lawrenceville to be part of the Food Waste Warriors program, conducting food waste audits. They sorted milk, fruits, and vegetables left on lunch trays into buckets and weighed it all. They were shocked that the school had trashed almost 600 pounds of food — in one day.

Thirteen Gwinnett County Schools completed the 31 food waste audits for the WWF’s Food Waste Warriors report. The data for Gwinnett County Schools was eye-opening: On average, 95,169 pounds of food per school, per year was wasted, and 49.4 pounds of food per student, per year was wasted, as well as almost 56,000 cartons of milk per school, per year.

READ MORE

California’s food recovery program is the first of its kind in the country.

The first 31 audits launched the ongoing relationship with the WWF and Gwinnett County Schools, which continues to focus on K-12 education. Today, the Food Waste Warriors program is a critical part of the Green and Healthy Schools and STEAM education within Gwinnett County Schools, which is the largest in Georgia.

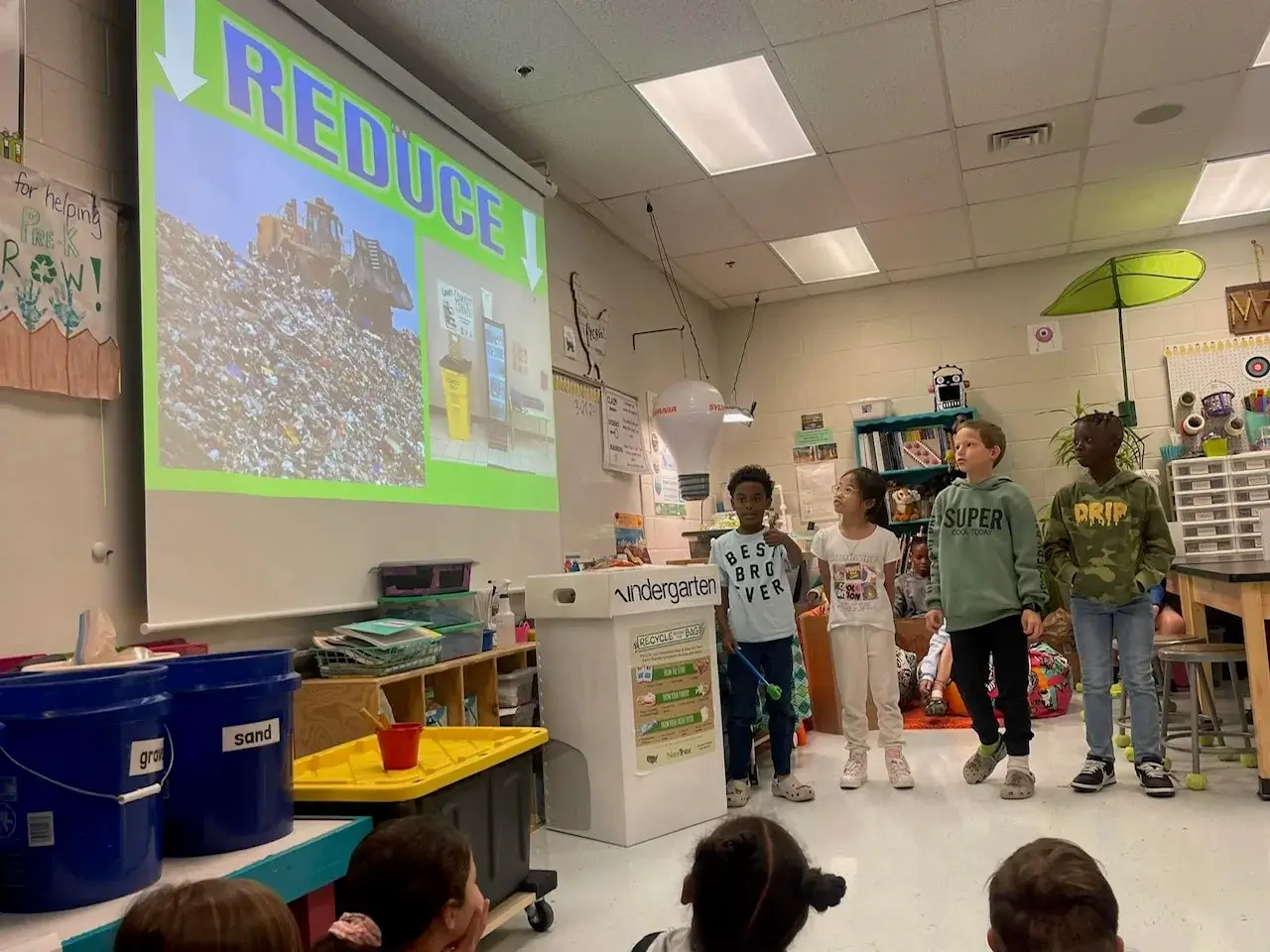

“The most important thing about the Food Waste Warrior program is the students tackle every aspect of the project,” says Brenda McDaniel, environmental education manager, Gwinnett County Schools. “It’s not just about doing food waste audits; the students must come up with solutions to tackle the problems.”

That first student-led audit at Lovin Elementary provided the school with different resolutions it has now implemented, including serving food differently to reduce packaging waste, eliminating straws and breakfast cutlery, and using biodegradable trays.

Third-graders now collect food scraps that would be trashed at the end of lunch and add them to the compost bin that’s part of the Food Well Alliance’s Compost Connectors program. They learn about composting in STEAM classes and how to use it to fertilize their gardens and help feed the school’s chickens.

First- and third-graders have improved their skillsets in science and math so much, the county revised its middle school curriculum to accommodate their new abilities.

“I never envisioned where this would go,” says Bassett. “We just wanted to change policy on how to reduce waste in cafeterias. That led to systemically building this culture around agriculture, nature-based learning, biology and engineering. Reducing food waste is just a small part of it.”

Raccoon Eyes

Georgia Tech in Atlanta is synonymous with engineering, prestigious research and cutting-edge technology. Soon, its dining services could be a leader in what universities can do to cut down on food waste in their dining halls, thanks to Tech students Bruce Tan, Ivan Zou, and Nathanael Koh.

The three students focused their CREATE-X Capstone, which is an undergraduate senior design course for entrepreneurial projects, on reducing food waste on campus because of the amount of food being trashed in the university dining halls. Their solution: Raccoon Eyes.

“The eye-opener for me was a time I was in the kitchen at the end of lunch service,” says Zou. “A worker pushed in carts full of food that were going straight to the trash.”

Raccoon Eyes has two components: 3D cameras and a computer screen on the dining hall trash cans. The 3D cameras take pictures of every plate and calculate the type and weight of food waste going into the trash using software the three students developed. The computer screen uses visual and audio to collect feedback about the food and to nudge students about future food waste.

During the period between Jan. 11 and May 2, 2024, the system tracked and measured the amount of food waste on more than 240,000 plates at Tech. While there was still about an ounce of food left on each plate, the overall amount of food being tossed dropped by 19 percent during the semester.